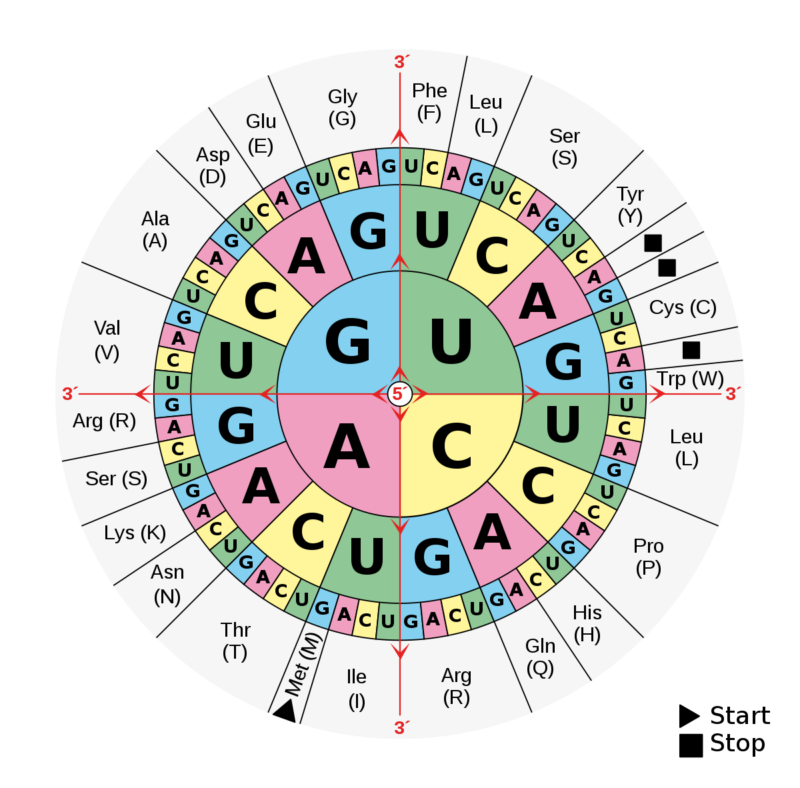

Enlarge / The genetic code. Note that a lot of the amino acids (the outer layer, in grey) are encoded by several sets of three-base codes that share the first two letters. (credit: Wikipedia)

Mutations are the raw ingredient of evolution, providing variation that sometimes makes an organism more successful in its environment. But most mutations are expected to be neutral and have no impact on an organism's fitness. These can be incredibly useful since these incidental changes help us track evolutionary relationships without worrying about selection for or against the mutation affecting its frequency. All of the genetic ancestry tests, for example, rely heavily on tracking the presence of these neutral mutations.

But this week, a paper provided evidence that a significant category of mutations isn't as neutral as we thought they were. The big caveat is that the study was done in yeast, which is a weird organism in a couple of ways, so we'll have to see if the results hold in others.

True neutral?

One of the reasons that most mutations are neutral is that most of our DNA doesn't seem to be doing anything useful. Only a few percent of the human genome is composed of the portion of genes that encode proteins, and only some of the nearby DNA is involved in controlling the activity of those genes. Outside of those regions, mutations don't do much, either because the DNA there has no function or because the function isn't very sensitive to having a precise sequence of bases in the DNA.

Read 16 remaining paragraphs | Comments