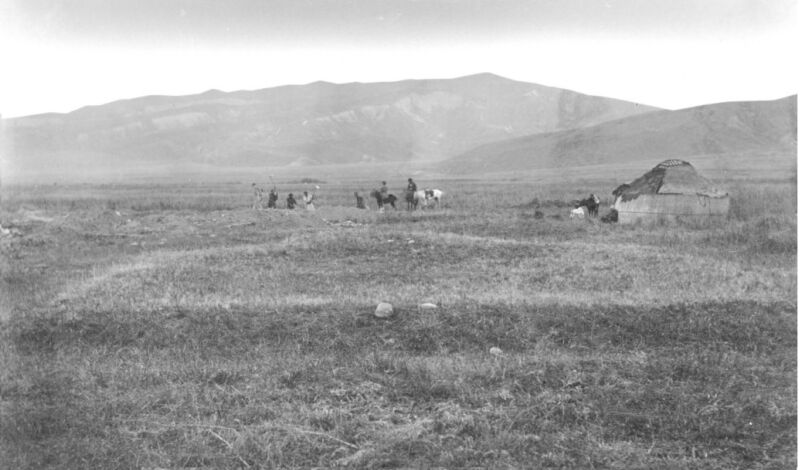

Enlarge (credit: Spyrou et al. 2022)

In 1338 and 1339, people were dying in droves in the villages around Lake Issyk-Kul in what’s now northern Kyrgyzstan. Many of the tombstones from those years blame the deaths on a generic “pestilence.” According to a recent study of ancient bacterial DNA from the victims’ teeth, the pestilence that swept through the Kyrgyz villages was Yersinia pestis—the same pathogen that would cause the devastating Black Death in Europe just a few years later.

Ground zero for the Black Death?

In just five years, bubonic plague killed at least 75 million people in the Middle East, northern Africa, and Europe. Known as the Black Death, the cataclysm of 1346-1352 is still the most deadly pandemic in human history. But the Black Death was only the first devastating wave of what historians call the second plague pandemic: a centuries-long period in which waves of Y. pestis periodically burned through communities or whole regions. When English diarist Samuel Pepys wrote about the Great Plague of London in 1666, he was describing a later wave of the same pandemic that began in the mid-1300s with the Black Death. Centuries of life with the reality of the plague actually shaped the genetic diversity of modern European populations.

And like every pandemic, the second plague pandemic had to start somewhere.

Read 14 remaining paragraphs | Comments